Throne of the Crescent Moon est un film de Naruto datant de 2006 Un roman de fantasy sword&sorcery écrit par Saladin Ahmed, un américain d’origine arabe, dans un contexte très mille et une nuits. Marre de l’Europe Blanche chrétienne avec une touche de paganisme, enfin de la fantasy arabo-musulmane (avec une touche de paganisme) !

Il faut dire que c’était l’argument marketing le plus martelé, je crois. Dans un climat où on plaint le monde trop blanc de The Witcher, ou qu’on dit sans peine et sans nuances que Tolkien est un suprémaciste blanc, et que la plupart de la fantasy et de la science-fiction suit encore cette impulsion, de toute évidence, ça devait résonner.

Comme le note une autre review :

Too often, a writer will appropriate elements from another culture and use this to add « exotic » qualities to a story that could, with minor alterations, be told in almost any locale. Arabic (in which I include societies from the Arabian Peninsula to the Leventine coast to Egypt to the Maghreb) culture, rich with fascinating stories and exquisite poetry, has often over the past few centuries been the subject of such appropriations. Orientalist literature, even when penned by talented writers such as F. Marion Crawford’s Khaled, William Beckford’s Vathek, or George Meredith’s The Shaving of Shagpat, so often reduces the source culture’s material to a distorted, wan shadow of its true glory.

C’est vrai. Je crois que pas que ce soit une question de gloire, mais c’est vrai.

So when I learned that Saladin Ahmed (whose « Hooves and the Hovel of Abdel Jameela » I marked for consideration for the aborted Best American Fantasy 4 anthology in 2010) had a debut novel, Throne of the Crescent Moon, due to come out this month, I was intrigued. I was curious to see how an American of Arab descent would go out portraying elements of Arabic culture in a secondary-world fantasy setting.

Pareil.

What I found was a rich, excellent tale (one that I suspect is but the opener for a series of tales in this setting) that utilizes the best qualities of several genres of fiction, including sword and sorcery adventure tales, to create a memorable tale.

Ah non, là pas du tout.

Plan

- Histoire

- Introduction

- Trials and errors, friends and enemies

- Showdown

- Fin

- Mes problèmes

- Ctrl-c ctrl-v buzzwords

- Platitudes

- Personnages féminins forts

- Almanach Punchline : Traditions et Heavenly Chapters

- Pratique musulmane ? Théologie musulmane ?

- Conclusion

Histoire

Commençons par l’histoire, que je vais décrire linéairement.

1. Introduction

Ca ouvre avec une scène de torture en prologue, un garde dans une boîte, qui se fait torturer par un type au kaftan sale. Voilà c’est énigmatique, In Media Res.

Adoullah est le dernier chasseur de Goules de Dhamasawat. On le sait parce que le début c’est

Dhamsawaat, King of Cities, Jewel of Abassen

A thousand thousand men pass through and pass in

Packed patchwork of avenues, alleys, and walls

Such bookshops and brothels, such schools and such stalls

I’ve wed all your streets, made your night air my wife

For he who tires of Dhamsawaat tires of life

DOCTOR ADOULLAH MAKHSLOOD, the last real ghul hunter in the great city of Dhamsawaat, sighed as he read the lines.

Et la copie sans honte de la citation de Samuel Johnson sur Londres devrait nous mettre sur la voie. Enfin, Adoullah est un vieux et gras chasseur de goules, son acolyte, Raseed Bas Raseed est un jeune Derviche de l’Ordre (juste l’ordre) armé d’une zulfiqar, ensemble ils tabassent des trucs et on vient justement les chercher pour un job de tabassage de trucs. Adoulla rencontre un de ses potes et ils s’insultent pour rigoler.

Des gens se sont fait tuer par des goules. Trois goules ! C’est étrange, avant des gens arrivaient à faire marcher des armées entières de goules mais maintenant c’est extrêmement rare de voir des sorciers capables d’en contrôler plus que deux à la fois ! Elles ont tué la famille d’un garçon, Faisal, qui se trouve être le petit-neveu de Miri, le grand amour d’Adoullah (mais ils ont rompu parce que sa vie de tuage de monstres est trop exigeante).

Prenant un tissu tâché du sang des victimes, il pense pouvoir faire un sortilège pour les localiser. Ils partent, et commencent à traverser la ville encombrée, quand ils tombent sur une estrade où va avoir lieu une exécution. Un garçon qui vola pour nourrir sa famille. Horreur ! Adoullah lamente que le calife actuel soit bien plus vil que son père, quand tout à coup, un carreau d’arbalète tue le bourreau, et Pharaad Az Hammaz, The Falcon Prince surgit. C’est un Prince des Voleurs, un mélange d’Esmeralda et d’Aladin. Il harangue la foule contre les méchant Calife qui arnaque le peuple :

“God’s peace, good people of Dhamsawaat!” The thief boomed, his outstretched arms embracing thecrowd. “Our time together is short! Hear the words of a Prince who loves you!” A small, cautious cheer went up from a few corners. “I’ve freed an innocent boy from the Khalif’s headsman. His crime? Being fool enough to think he could pick coins from a watchman’s purse and feed his ailing mother! Now, we grown folk know that watchmen are as attached to their purses as normal men are to their olive sacks.” The bandit grabbed at his crotch and the crowd laughed hesitantly at his bawdiness. “But did the child deserve to die? Do we Dhamsawaatis care more for the ill-earned wealth of bullies than for the life of a child?” (p. 38)

Haha, couille-bite.

Détail que je trouve au moins intéressant : il use d’un sortilège qui fait que tout le monde le voit et l’entend pour s’adresser à la foule. Mais bref, alors que les gardes peinent à venir sur l’estrade à travers la foule qui chante les louanges du Falcon Prince, il disparaît dans un nuage de fumée — surprise — et s’enfuit.

Raseed et loyal-bon du coup il aime pas les voleurs, mais Adoullah est chaotique bon du coup il aime bien, trop le débat moral. Adoullah en profite sinon pour pointer qu’il aime pas la virginité de Raseed :

His assistant was a true dervish of the Order, truer than most of the hypocritical peacocks who wore the blue silks. He had spent years hardening his diminutive body, his only purpose to be a fitter and fitter weapon of God. To Adoulla’s mind, it was an unhealthy approach to life for a boy of seven and ten. True, God

had granted Raseed more than human powers; armed with the forked sword of his order, he was nearly invincible. Even without the sword the boy could take on half a dozen men at once. Adoulla had seen him do it. But the fact that he had never so much as kissed a girl lessened Adoulla’s respect for him considerably. (p. 27)

Il a 17 ans mec calme-toi. Mais serais-je en train de sentir un character arc ?

A long-haired girl in a tight-fitting tunic walked by, and Raseed knew that Almighty God was testing him yet again. He averted his eyes and smothered the shameful ache that began to fill his body. (p.48)

Ok tu as effectivement 17 ans mais calme-toi aussi.

Alors qu’ils passent par une ruelle, ils tombent sur le Falcon Prince en train de s’échapper. Raseed veut lui péter la gueule, mais Adoullah veut le couvrir parce qu’il aide les pauvres. Quand les gardes arrivent, Adoullah les envoie dans l’autre direction.

Ils sortent enfin de la ville, et fait son sortilège avec des aiguilles sacrées et des prières.

The Doctor had pulled out a bit of paper, the bloody scrap of the child Faisal’s clothing, a vial, and a long platinum needle. He wrote something on the paper, pricked his finger with the needle, and pinned cloth and paper both to the ground. Then he stood, closed his eyes, and recited from the Heavenly Chapters, sprinkling out a dark green powder—mint?— with each Name of God he spoke. “ ‘God is the Seer of the Unseen! God is the Knower of the Unknown! God is the Revealer of Things Hidden! God is the Teacher of Mysteries!’ ”

Nothing happened, so far as Raseed could see, but the Doctor, his brow sweaty now, opened his eyes and took his mule’s rein from Raseed.

He remounted and continued down the road. He said nothing, not even turning to see if Raseed was following. As Raseed mounted and trotted up beside the Doctor he realized why. He’s winded—the traveling, the spell—it’s all taking its toll on him. Raseed tried not to be worried by this. Raseed gave the Doctor a few minutes to catch his breath before he spoke. “You have found the ghuls’ trail, Doctor?”

“Aye,” was all the Doctor said. (p.53)

Ils marchent ensuite, Adoullah suivant les voix dans sa tête, quand tout à coup il se fait attaquer par du foreshadowing :

“Stop.” The Doctor spoke the word loudly enough to startle two marshbirds into flight. It was the first time he’d spoken in a long while. “The trail veers off here, but something is not quite right.”

“What do you mean, Doctor?”

Raseed’s mentor looked truly confused—a rare sight.

“I don’t rightly know, boy. In all my years of casting tracking spells, nothing like this has happened. Normally I feel—maybe better to say I hear within my mind—God’s prompts in the direction of my quarry. And this is still the case. Our prey is close and in that direction.” The Doctor pointed off the road to the left, toward a dense patch of boulders and a lone hill with a pointed top. “But I also hear His hints about other dangers. ‘The jackal that eats souls.’ ‘The thing that slays the lion’s pride.’ I . . . I don’t know what it means. In all my years I’ve never . . .”

The Doctor let go of his reins and held his head in his hands. Raseed tried to hide his worry.

The Doctor took a deep breath and noisily exhaled.

He looked up, shook his head, and ran a hand through

his beard. “Gone. Whatever it was, it’s gone.” (pp. 54-5)

Et là ils trouvent des Bone Ghuls, donc des cadavres réanimés. Ils les tabassent, mais manquent de se faire tuer, quand une lionne arrive et en dézingue un. Il s’agit d’une shapeshifteuse, une she-lion, une werelion, Zamia Banu Laith Badawi, les Laith Badawi étant un clan bédouins qui ont parfois la faculté génétique de se changer en lions. Notez d’ailleurs que Laith Badawi (ليث بدوي) signifie littéralement « lion bédouin », plus original que Simba qui veut dire lion en Swahili ou Remus Lupin le Werewolf McWolf.

Bref, elle fait la dure malpolie, elle est une bédouine, mais elle fond subitement en larmes, repensant à son clan qui s’est fait massacrer par ces goules. Elle les a trouvés avec les yeux rouges brillants, ce qu’Adoullah pense être de la soul-magic, quelqu’un devorant leurs âmes. Des yeux d’une couleur intense pour démarquer que les personnages ont perdu leur statut humain hmmm original hmmmm.

Malgré les grands articles d’Ahmed sur comment moâ j’écris des personnages féminins FORTS et BIENS [février 2011], Zamia a apparemment épuisé son quota d’activité, puisqu’elle est maintenant en position de faiblesse — comme pratiquement toujours dans la suite de l’histoire. Et d’ailleurs comme elle a 15 ans, elle devient subitement et irrésistiblement attirée par le mâle d’âge compatible le plus proche, Raseed, 17 ans.

Dieu du ciel que l’histoire d’amour entre Zamia et Raseed est mal goupillée. Ils ne parlent pas, ils tombent juste follement amoureux l’un de l’autre et se regardent bizarrement pendant que tout le monde leur dit « HOHOHO c’est évident que vous êtes amoureux même si vous êtes un peu confus huhuhu !!! » c’est tellement original et pas douloureux à lire.

Raseed was clearly preoccupied as they set to their bread and broth. There was more to it than the horrors and wonders they’d seen today. Adoulla knew the cause, though he doubted the boy had yet admitted it to himself. The girl.

No doubt the dervish was twisting himself in knots trying to square the circle of his pious oaths with a young man’s natural reactions, and only half aware he was doing so. When Adoulla was a young man, he would have told the girl that she had a lovely face and been done with it. Though this particular girl did not have a lovely face, exactly. (p. 77)The way the dervish stood and spoke made Zamia want to be nearer to him. Were she not lying down, she feared she would have taken a step toward him against her will. (p. 167)

Raseed found that he was not disappointed. He found, in fact, to his shame, that he could not look away from that smile. He found that Zamia’s little laugh cut through him like a sword poisoned with pure happiness. He tried to force his disciplined eyes to look away, but he could not. Zamia turned and looked directly at him. As her green-eyed

gaze met his, and she saw him staring at her, a look of pure terror replaced the smile on her face. She covered her mouth with her hand and bowed her head again. He followed suit, casting his eyes to the neatly swept stone floor. You were staring at her! You were staring at her, and you’ve shamed her. Have you no shame? Do you serve God or the Traitorous Angel? (p. 269)

2. Trials and errors, friends and ennemies

Revenons à l’histoire, qui entame je pense sa partie centrale, où ils tentent de décrypter le mystère de ces super-goules. Zamia tend une lame imbibée de sang, que son père a brandi contre les agresseurs avant de mourir. Les goules n’ont pas de sang ! Adoullah pense qu’il pourrait s’agir de celui leur maître, à n’en pas douter un serviteur de l’Ange Traître. Cependant son sort de localisation ne fonctionnera pas, mais il connait quelqu’un, en ville, qui pourrait l’aider à faire un meilleur sort de localisation. Ils dorment pour repartir le lendemain matin.

Just as her thoughts went to last night’s battle and to her new allies, she caught the approaching scent of the dervish Raseed. A half moment later, the lithe little holy man peeled himself from the shadows of a rock not ten feet away. She felt a flash of shame—no man or animal had ever gotten so close to her without her scenting them before! The last traces of the ghul pack’s corrupt stench had blown away on the night wind, and she was better rested than she had been the night before. She had no excuse! But when she did get a clear scent on the dervish she was shocked out of her self-scolding. Ministering Angels help me! She had never been in the presence of a scent that was so strong, yet so clean. Zamia found her shame deepening, but for new reasons. (pp. 80-81)

Dieu que c’est mauvais. Ils repartent donc avec Zamia et résolvent de dormir chez Adoullah en attendant. Vous faîtes que de dormir, bordel. Zamia, malgré le fait que son clan commerce beaucoup avec les villes ne pige pas grand-chose à la ville et ne cesse de dire des trucs tribaux.

“What I want to know,” she asked, “is whether we are truly safe here, Doctor. I do not wish to wake to the feeling of my ribcage being cracked open. The one whose ghul pack we fought—what is to stop him from striking us here?”

The Doctor yawned and smiled patronizingly. “Sneaking ghuls about within a city is no easy matter, child. And besides, my home is charmed so that no ghul can cross its threshold.” (p. 101-2)

Je me demande si ils vont se faire attaquer par des goules dans leur sommeil.

Nouvel interlude où on revoit le garde en train de se faire torturer avec un type qui dit des trucs énigmatiques, parlant de lui même à la troisième personne en tant que Mouww Awa.

Environ trois lignes plus bas, nouveau chapitre : ils sont attaqués par des goules dans leur sommeil.

Pour la faire court, le combat fout le feu à la maison et Zamia est blessée par une créature à tête de chacal qui semble faite de ténèbres. Vous avez deviné. Le royaume de Kem, étant bien sûr l’égypte, ils se font donc attaquer par un démon-dieu égyptien Anubis/Seth, qui a les yeux rouges (comme les victimes de mangeage d’âme) qui a pris possession d’un type, un peu comme cet épisode de Samurai Jack (3×5) vous savez :

No! Mouw Awa the manjackal is unseen and unheard by men until he doth strike. But the kitten hath scented him!

The thing before her was shadow-black, save for glowing red eyes. Somehow she heard its words with both her ears and her mind. The creature held a vague shape—something like a jackal walking about on a man’s two legs. But the edges of its outline whipped and wavered like tent flags in the wind. The reek of her band’s death wafted from the creature. The smell of burnt jackal-hair, and of ancient child-blood.Its eyes. They were a brighter version of what she had seen in her dead bandsmen. And looking at the abomination before her, Zamia knew that it wasthis thing that had eaten the souls of her band—of her father. She screamed in fear. The thing lunged at her again, and she barely managed to dodge back from its shadow-wrapped fangs. She shouted.“RASEED! DOCTOR! ENEMIES!”(pp. 107-8)

Zamia saute sur Mouw Awa est blessée du coup Adoulla appelle un couple d’amis alchimistes/mages qui peuvent la soigner, Litaz et Dawoud coup de bol c’est eux qu’il projetait d’aller voir le lendemain.

C’est là qu’on commence d’ailleurs des chapitres POV, du point de vue de l’un ou l’autre personnage qui rallongent énormément la narration pour bien peu de valeur ajoutée en vie intérieure. Zamia va bien sûr très mal et risque de mourir sa blessure semble attaquée à l’acide, etc. On a besoin de « Crimson Quicksilver » pour la soigner donc Raseed va faire les courses. Cependant l’apothicaire n’a plus qu’une fiole — tout le monde se les arrachant parce que ça permet de régénérer le sang — qu’il doit garder pour les vils contrôleurs d’impôts du calife. Là, ils se font attaquer par des hommes de Pharaad Az Hammaz qui veulent lui subtiliser une poudre bleue aux propriétés magiques. Raseed les met en déroute, mais d’un seul coup il tombe à terre, fauché par un sortilège lancé par quelqu’un hors de la boutique. C’est Pharaad Az Hammaz le Falcon Prince. Il jette encore un sort de nausée à Raseed et lui dit que le produit ne fera effet qu’une heure. Raseed lui court après malgré la nausée, Pharaad Az Hammaz estimpressionné par ses compétences au combat, malgré le sortilège. Dopé à divers sortilèges qui lui permettent de sauter d’immeubles en immeubles, il le bat par contre et lui lance une fiole. La fiole de crimson quicksilver !

Hé oui il a entendu ta discussion avec le marchant et a décidé pour quelque raison de te donner cette fiole. Bon. Par contre, dit-il le sceau sur le flacon s’est brisé, du coup tu n’as qu’une heure pour le ramener à bon port où l’air le corrompra ! Oui, ou fermer le flacon de nouveau enfin bref. On dirait une mini-quête stupide d’un jeu Assassin’s Creed, ce qui n’apporte d’ailleurs rien : il ramène la fiole.

Pendant ce temps, Adoulla se morfond d’avoir perdu ses livres et son matos magique dans l’incendie. Il se souvient d’un livre qu’il avait prêté à Dawoud et qui parlait justement de Mouw Awa et Abu Nawas, les noms que se donnait la créature à tête de chacal. Il s’agissait d’un tueur d’enfants –pédophile ? — qui a été scellé dans un monument de Kem après sa mort, c’est du moins ce que racontent ces mémories de cour. Abu Nawas est donc apparemment ressuscité par les dieux/démons égyptiens parce que c’était pas une super idée de l’emmurer dans une pyramide.

Dawoud va lancer son sort de détection à partir du sang sur la lame de Zamia, que sa femme Litaz a analysé. Et stupeur ! C’est méchant !

“Well, whatever its source, it is the strangest blood I have ever seen. Full of life and lifeless. All of the eight elements are here, but they are . . . negated somehow. Sand and lightning, water and wind, wood and metal, orange fire and blue fire! How could they all be in one drop of blood, and yet not be there?” The little woman turned to her husband. “Stranger still, within the clots there are creeping things moving about. It is as if this blood came from some mix of man and ghul. It makes no sense. Still, my love, you should work your magics here. God willing, they may give us better answers.” Using a tiny silver spoon, the alkhemist scooped a bit of white powder from a jar into a glass vial filled with red liquid. The liquid began to bubble and froth and turned bright green. Litaz then took this liquid and poured it over the bloodied knife that had been Zamia’s father’s. A bright green light began to shimmer off of the knife. The light grew brighter and brighter until it filled the room.“You can begin,” the Soo woman said to her husband. “Stand back,” she said to the others, doing so herself as she spoke. The magus stepped forward, placing his gnarledhands a hairsbreadth above the knife. An eerie green light began to glimmer about his fingers as they weaved back and forth around the blood-stained blade. The old Soo’s eyes rolled back, and he chanted a wordless chant in an oddly echoed voice. Wicked magics, Zamia thought. Instinctively, she started to take the shape . . . And of course found that she couldn’t. Panic rose in her again—she could feel the shape just beyond her reach, and feel the pain of her wound keeping her from her lion-self. Almighty God, I beg you, help me! But then the magus was speaking, and she had to heed his words, for that was the path to vengeance for the Banu Laith Badawi. Tears burned in her eyes, but again she shoved thoughts of the shape aside and listened. “This blood is like . . . like the cancellation of life,” Dawoud said as his long dark fingers darted back and forth above her father’s knife. “More than that, the cancellation of existence. Like the essence of a ghul, whose false soul is made of creeping things. But with will. Cruel, powerful will.” (p.181-2)

Ensuite Dawoud se fait attaquer par du foreshadowing comme Adoulla plus tôt :

The old Soo was touching the knife now with his fingertips, and he screamed. It was a wordless screaming chant at first, but the pain-laced sounds resolved into words:

“THE BLOOD OF ORSHADO! THE BLOOD OF ORSHADO!” The magus’s body jerked about strangely as he screamed, but he kept his hands on the knife. “THE BLOOD OF ORSHADO!” (p.183)

Orshado semble être une sorte d’Antéchrist, de Ghul of Ghul. Tout comme le kaftan des chasseurs de goules est magiquement blanc pur, son kaftan est magiquement sale. C’est lui qu’on voyait dans les interludes avec Abou Nawas en train de torturer un garde. Les aventuriers concluent qu’il faut avertir le calife. Dawoud connaît un type de la garde du calife, du coup il pense aller l’avertir des complots. Ca prend tout le chapitre, il se fait même convoquer devant le calife et essaie de l’avertir, mais se fait engueuler parce que le calife est méchant.

Adoulla va voir Miri, la femme sur laquelle il fantasme depuis le début du roman. Elle a un nouveau copain ce qu’Adoulla n’aime pas, et va même le marier. Il dit en gros que c’est pas juste parce qu’il peut pas se marier parce qu’il doit sauver le monde mais il aimerait bien la marier. Elle lui dit qu’elle se fiche de son avis et que tout est fini entre eux et que comme lui va jamais l’épouser hein arrête la jalousie. Il promet que c’est sa dernière affaire de goules et après il la demande en mariage. Elle y croit pas alors il le jure devant dieu. Bon.

Il lui demande des informations sur Abou Nawas ou Mouw Awa et elle révèle l’existence d’un rouleau (un parchemin) qui parlerait du Cobra Throne. Elle dit que le Falcon Prince s’y serait interessé tout comme le calife mais qu’en définitive ça aurait coûté trop cher de le traduire alors il a pourri dans un coin. Adoulla lui promet solennellement la marier après cette dernière mission – même s’il l’a déjà fait plein de fois.

Du coup comme littéralement tous les problèmes sont résolus par « je connais un type qui », Litaz connaît un type riche, Yaseer, qui pourra utiliser ses sortilèges pour décrypter le parchemin. A l’aller, elle et Raseed se font attaquer par des Humble Students, des moines puritains chiants, vêtus d’une bure attachée d’un cordeau, qui enquiquine une fille suspectée de se prostituer. Litaz lui demande son nom et :

“Suri,” Litaz repeated. “A beautiful name. And a very, very old one.” She turned to the Students with a clearly forced smile. “Surely you brothers see the sign from Almighty God here? The Heavenly Chapters’ story of Suri says ‘O Headsman, drop your sword and serve His mercy! O Flogger, drop your whip and serve His mercy!’ ”

The gray-haired Student spread a conciliatory hand, but he sneered as he did so. “The Chapters also say ‘And yea, proper punishment is the sweetest mercy,’ do they not? A new era is coming, outlander! An era when only those who walk the path prescribed will prosper.”

Bon étant donné qu’ils sont xénophobes et misogynes, on comprend assez bien qu’on les aime pas. Litaz en met par terre avec une dague qui a un compartiment qui tire des soporifiques et Raseed tabasse le reste. Ils arrivent chez Yaseer, qui est amoureux de Litaz mais va pas le faire pour ses beaux yeux alors ça fera plein d’argent pour récupérer le parchemin décrypté. En sortant, ils se font attaquer par lesdits Humble Students qui ont rameuté la garde. Le riche type sort le sceau du calife pour montrer qu’il est important et les disperser, disant que Litaz lui en doit une mais on s’en fout parce que tout ce personnage était inutile. Rajoutez des discussions où il tente à moitié de séduire Litaz et dont on se fout complètement. (Ca dure dix pages ! Ca n’apporte rien !)

Ils rentrent pour se préparer à manger le festin de la Feast of Providence (jour le plus court de l’année) et entendent que le sortilège de décryptage étant fini ils peuvent lire la prophétie (original !) à tout le monde :

“No one knows how the Throne of the Crescent Moon was made. And few know that it was once called the Cobra Throne. Its great curved-moon back, which was once carved in the shape of the Cobra God’s spread hood, takes no mark or burn. The Kemeti Books of Brass, lost to us now, claimed that the Faroes, called also the Cobra Kings of Kem, sat upon it for their coronations, just as the Khalifs would come to do. But though the Khalifs have sat on it in coronation for centuries, there are those who say they know not its true power. That the throne was ensorcelled with unseen death-diagrams; bewitched by the Dead Gods, who loved treachery. That this power could be called only by spilling the blood of a ruler’s eldest heir upon it on the shortest day of the year. The Books of Brass claimed that he who managed to drink blood so spilled would be granted command of the most terrible death magics the world has ever known—master of the captive souls of untold numbers of long-dead slaves.The dark arts of the Cobra Kings, scoured from the world by God, would return.” (p. 271)

Oh non ! C’est aujourd’hui ! Qui eût cru que la prophétie que l’on n’a décrypté que récemment et à la suite d’un concours de circonstance fortuit devrait se produire aujourd’hui ! Quel coup de chance ! Quelle fatalité !

Vient maintenant le showdown.

3. Showdown

C’est basiquement la fin de tous les Zelda du monde : la prophétie se finira aujourd’hui et les forces des ténèbres vont tenter d’infiltrer le palais, donc on doit aller les taper, dans le palais.

Avant ça, un interlude qui montre encore le garde torturé, qui du coup fait partie du plan de Mouw Awwa et Orshado pour s’emparer du Cobra Throne. Torturé, il commence à se rappeller qui il est.

And suddenly, a whole piece of the guardsman’s mind slid back into place. He was Hami Samad, Vice Captain of the Guard, and there was nothing he could do but beg for his life through a cracked throat. “Please, sire! I will tell you whatever you wish! About the Khalif, about the palace!” He began to weep wildly. “Ministering Angels preserve me! God shelter me!” The gaunt man stared at Hami Samad with black-ice eyes. The guardsman felt the gaunt man’s spindly fingers dig roughly into his scalp. The gaunt man’s eyes rolled backward, showing only whites. Horrible noises filled the room, as if a thousand men and animals were screaming at once. There was a tearing noise, and there was pain a thousand times more searing than anything he had yet felt. Impossibly, he felt his head come away from his body.

Impossibly, he heard himself speak. “I AM THE FIRSTBORN ANGEL’S SEED, SOWN WITH GLORIOUS PAIN AND BLESSED FEAR. REAPED BY THE HAND OF HIS SERVANT ORSHADO. THE SKINS OF THOSE-WHO-WERE- BELOW- ME SHALL MOVE AT THE MUSIC OF MY WORD. ALL OF THOSE BENEATH SHALL SERVE.”

The last thing he saw was Hami Samad’s headless body in a great iron kettle, spurting blood that mixed with a molten red glow of boiling oil. (pp. 282-3)

En chemin, ils se font arrêter par un garde, mais qui se trouve être à la solde du Falcon Prince. Il les emmène dans un coin et pouf ! Le Falcon Prince. (ok j’ai pas bien gardé la surprise).

Donc on le rejoint et on décide de s’allier temporairement pour empêcher Orshado de s’emparer des pouvoirs du Cobra Throne. Ils passent par un souterrain qui les mène au coeur du palais, le Falcon Prince a répandu partout la poudre bleue qu’il a volé à l’apothicaire, qui étouffe les sons. Mais quand ils attaquent le calife, ce dernier active un système de protection magique qui fait se lever des murs et sépare les compagnons.

“You . . . you’re . . . how did . . . ?” the Khalif stammered without one whit of court-phrasing in his speech. “No intruder could have made it into . . .” He fell silent, clearly at a loss. He looked at Dawoud, and his kohl-lined eyes grew even wider. “You! Where did—?” “No questions, tyrant!” the Prince shouted, his mad eyes ablaze with crazed purpose. “But I have a question for you! How does it feel to—” The Prince’s words were cut off as the Khalif touched one of his rings and a flash of light filled the room. Adoulla, sensing danger in that way that had become second nature over the decades, dashed toward the Khalif, and he saw Pharaad Az Hammaz do the same. Something slid into place behind him, and before him, he saw a thick panel of wood slide down from the ceiling, cutting him off from the Khalif. False walls, he realized, and they had cut him off from his friends as well. The Falcon Prince stood beside him, pounding on the panels with the pommel of his sword. “God’s balls!” the thief shouted, “These are made of ensorcelled wood. That sneaky son of a whore! Though in truth, I suppose it’s no great matter. Dispatching him first would have helped, but he is not my true quarry anyway. In a sense, this makes things easier for us—he is cut off from the Heir.” (p. 316)

Le Falcon Prince va chercher le vrai prince pour l’utiliser dans son rituel et obtenir les pouvoirs du bien. Et c’est le twist :

The boy had the same face-shape as the Khalif. The Heir. Little Sammari akh-Jabbari akh-Khaddari sat cross-legged on a cushion in the center of the room, a huge illuminated book open before him. His mild expression was replaced with shock as he seemed to suddenly notice the mad racket filling the palace. Adoulla guessed that there had been a silencing spell cast on the brass door. So much money and magic wasted on sheltering these fools from unpleasantness. “You—You are—You are him,” the boy stammered with a bit more grace than his father had. “The Falcon Prince!”

“INDEED I AM, O TYRANT-IN- TRAINING!” the Prince boomed, advancing with his sword still drawn on the timid-seeming boy, who was practically bowled over by the sound. “I am the Falcon Prince, and my wrath is terrible! I have come to—”

“You are my hero,” the boy said quietly, brushing a strand of long black hair from his face.

« I warn, you, spawn of a—eh?” Pharaad Az Hammaz blinked, his bombast dropping away. It was the first time Adoulla had seen the thief look unsure of himself. “What did you say?” The boy looked ashamed that he had spoken, but he repeated himself.

“I said ‘you are my hero.’ ” The Heir looked at Adoulla, but only seemed to half-see him. (p. 319-320)

A cause des histoires qu’il lit, il adore le romantique Falcon Prince, contrairement à son méchant papa. Il va au moins défendre son père ? Non :

“But what of my father, O Prince? What of me?”

“Your father has the blood of many men and women on his hands, Sammari akh-Jabbari akh-Khaddari. But if you aid me in this, I will let you and him go peacefully into exile, perhaps to—”

“No,” the boy interrupted with an air of easy command that belied his bookish appearance. “If you want my help with this, O Prince, you must kill my father. I have sworn an oath before God that I would see him dead.” Adoulla watched the Prince gape at the boy and didn’t doubt that he was gaping also.

“I . . . but. . . . Why . . . ?” Pharaad Az Hammaz stammered.

“You are wrong about my father’s laziness in killing, O Prince. Perhaps you have heard that my mother, God shelter her soul, died from a fever. She did not. I watched my father strangle her because he thought he had seen her make sugar-eyes at one of his aides. When I tried to stop him, he beat me. He said I would understand when I grew older. This was five years ago, before he became the Khalif. All I have come to understand in that time is that it is my sacred duty to see him slain.” (p. 322-3)

Du coup, même ça ne pose pas de problèmes et ils peuvent aller à la salle du trône pour que le garçon lui passe le pouvoir :

As the three of them walked, Pharaad Az Hammaz explained about the simple ritual that would allow the Heir to pass mastery of the throne’s beneficent magics and rulership on to the thief. He said nothing of the death-magics the throne held, or of the blood-magic version of the spell. “But what about recognition from the other realms?” the boy asked. “Rughal-ba? The Soo Republic?” The Prince shrugged his large shoulders. “Let me worry about that. I have diplomats and clerks-of- law working for me as well as thieves and sell-swords.” He winked at the boy incongruously. “Believe me, the clerks-of- law are scarier than the thieves! So. What say you, Sammari?” “I’ll give you the throne, O Prince. If you swear before God that you will use its power as a hero ought, and if you will kill the Defender of Virtue for what he did to my mother.” “I swear it before Almighty God, who witnesses all oaths.”(325-6)

Là ils arrivent dans la salle du trône et le calife arrive avec des gardes et des mages de la cour, Orshado (qui ressemble à Adoulla avec un kaftan sale) et Mouw Awwa arrivent (on sait pas où ils étaient ni ce qu’ils foutaient avant, , bref c’est la scène des portes dans l’épisode de Scooby-Doo qu’est cette conclusion. Mouww Awa tue le calife, et Orshado brandit la tête du garde (mais si dans les interludes) qui crie à nouveau, suscitant des skin ghuls :

Orshado withdrew a human head from the sack he held. In an unearthly voice, the head jabbered, “ALL OF THOSE BENEATH SHALL SERVE. ALL OF THOSE BENEATH SHALL SERVE.” All around Adoulla, the guardsmen’s eyes rolled back, their skin shriveled, and their mouths echoed these words. As one they turned on Adoulla, the Prince, and the Heir. In that instant, Adoulla knew, they had become something more and less than men. Skin ghuls. Monsters made by twisting a living man’s soul inside out. Even amidst all of the shocks he had seen in the past week, this was a shock to Adoulla. He had only ever read about them—had thought the foul art of their raising was thankfully lost to the world. Neither spell nor sword could destroy a skin ghul. The old books said that tainted flesh would rejoin tainted flesh and corrupt bones would reknit with corrupt bones until the death of the skin ghuls’ maker drove the malign false life from their stolen bodies. (p. 329)

Adoulla tente de créer un bouclier mais ça lui draine trop de force et alors que les goules l’assaillent, il semble s’évanouir.

La chapitre passe à Litaz qui continue la narration. Le groupe de potes curt après Adoulla. Zamia se change en lionne et suit sa piste. Ils tombent sur des skin ghuls

Skin ghuls. But they are just a legend. (p.327)

Merci Litaz. Ils arrivent à peine à les retenir, mais les deux gosses veulent se battre. Ils entendent Adoulla crier et foncent vers lui. Après n bref combat, Zamia égorge Mouw Awwa.

Apparemment le rituel de magie bénéfique dont on a appris l’existence y’a tris secondes ne marche pas :

Upon the dais was a high-backed throne of bright white stone. The Falcon Prince sat on the throne, hands clasped with a long-haired young boy by his side. Pharaad Az Hammaz was shouting. “It’s not working. IT’S NOT WORKING!” (p. 344)

Raseed se précipite vers Adoulla qui perd conscience et que ses yeux commencent à tourner rouge sang. Comment les arrêter ? lui demande-t-il, il dit juste « Orshado ».

Orshado. Then the ghul of ghuls himself must be beheaded!

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw gouts of magical flame—Litaz and Dawoud battling yet more skin ghuls. He didn’t know what had become of Zamia. Raseed laid his mentor’s big limp body carefully upon the dais. He looked up and saw Orshado leap impossibly—magically— onto the throne itself. The ghul of ghuls backhanded Pharaad Az Hammaz with a, no doubt, sorcerous strength. The master thief dropped his sword and fell from the throne onto the dais. Then Orshado, one foot planted on the throne, grabbed the child—the Heir, Raseed realized—by his long, jet-black hair and drew a knife. He’s going to drink the Heir’s blood, just as that scroll said. Orshado’s curved knife darted up and down, and the Heir screamed in pain. A red spray spattered Orshado’s kaftan. At the same time, the half-conscious Falcon Prince spoke a single word and made a strange gesture. Then he reached past the bleeding Heir and pressed something on one of the throne’s armrests. Raseed heard a loud click and a groan of shifting stone. Another secret that the Khalifs never learned of? It seemed so, for below him the floor swiftly receded as the throne and the entire dais it sat on—with Raseed, the Doctor, the Heir, Pharaad Az Hammaz, and Orshado all on it—rose on some sort of column. (p. 346)

Pourquoi pas, un mécanisme secret dans le trône qu’on apprend que maintenant.

Raseed veut tuer Orshado, qui continue à poignarder le prince héritier, mais une illustion s’empare de lui : le monde devient rouge et des hallucinations des hommes qu’il a tué se présentent à lui, lui citant les Heavenly Chapters et le vouant à l’enfer, mais il combat l’illusion et tue Orshado, pouf. Les skin ghuls s’effondrent et Rassed avec elles, exténué.

Adoulla reprend conscience. Il voit le prince héritier mort, et le Falcon Prince, qui a bu son sang pour se procurer les pouvoir des ténèbres finalement.

The Heir’s unmoving body was sprawled across the Throne of the Crescent Moon, which was spattered with the boy’s blood. Pharaad Az Hammaz was hunched over the dead Heir. And there was blood dripping from the man’s lips. Adoulla fell to his knees, and his joy at having dodged a dark death fled. He screamed wordlessly at the foul act he was witnessing.

The Prince looked at him, the guilt on his face as visible as the blood was. “The boy asked me to do this, Uncle. He knew he was dying.” His voice was a rasp, with none of its usual bravado.

The passing of the Cobra Throne’s powers through hand-clasping was a lie, it seems. Its feeding and healing magics were a myth. But the blood-drinking spell. The war powers. These are real. I can feel their realness coursing through me.” Adoulla wanted to vomit. He wanted to choke the Prince then and there. But it took all of Adoulla’s strength just to rise to his feet. He bit off angry words as he did so.

“He was a boy, you scheming son of a whore! A boy of not-yet- ten years!”

And, just like that, the madman’s smug mask dropped. “Do you think I don’t know that, Uncle? Do you really think my heart is not torn apart by this?”

“Better that your heart were torn apart by ghuls, than that this child should die. You are a foul man to do this, Pharaad Az Hammaz, and God will damn you for it.” The bandit wiped blood from his mouth onto his sleeve.

“Perhaps. I did not kill the boy, Uncle. But he is dead now. His father is dead. There will be a struggle for this damned-by- God slab of marble, and I will need all of the power I can muster if I am going to keep it from falling back to some overstuffed murderer who lives by drinking the blood of our city. What was I to do?” The smug smirk returned. (p.353-4)

Blablabla, Adoullah le tape, et le Falcon Prince va établir un royaume nouveau et plus juste blabla mais si il le fait pas Adoulla le tuera.

4. Fin.

La boutique de Litaz s’est faite brûler par les Humble Students alors Litaz et Dawoud se barrent dans le pays natal de Litaz.

Raseed veut continuer à faire partie de l’ordre pour gagner du galon désolé Zamia :

“But . . .” he continued, wishing he were dead, “but the Order forbids Shaykhs to marry. If I asked for your hand I would be turning my back on any chance of advancement in God’s eyes. I would forever remain a dervish in rank and would never be able to teach at the Lodge of God. Until I met you, I was certain that to ascend from dervish to Shaykh—to become a fitter weapon of God—was the kindest fate I could possibly pray for.” Zamia’s eyes were wet, but she shed no tears. She swallowed hard and it took every bit of training Raseed had to refrain from reaching out to her. “And now?” she asked at last. “Now . . . now I do not know. Perhaps I will return to the Lodge of God. I plan to leave this wicked city. That much I do know. After that. . . .” He trailed off, not knowing what else to say. (p. 363-4)

Adoullah demande sa main à Miri et FIN.

(Zamia n’a pas de storyline de fin.)

Mes problèmes

Ctrl-F Ctrl-H buzzwords

Franchement, tu prends A Song Of Ice And Fire, tu trouves beaucoup d’éléments communs, si ce n’est qu’ASOIAF, malgré ses défauts n’est pas aussi pesante lecture.

The Humble Students ressemblent trait pour trait aux Sparrows, ces moines puritains. Miri of A Hundred Ears qui a un réseau de mendiants et de prostituées qui lui disent tout (parce que ces populations très vulnérables n’ont que ça à foutre de risquer d’écouter aux portes) : on pense à Varys. Les yeux rouges des victimes d’Orshado font penser aux yeux bleus des White Walkers. Bien sûr ce sont des tropes beaucoup plus large, mais c’est bien le problème, j’ai déjà vu ça un milliard de fois. C’est pas parce que t’as remplacé « roi » par « calife », « tunique » par « kaftan » et « bière » par « thé à la cardamomme » que c’est plus divertissant.

Platitudes

Litaz rolled her eyes. “Right. I remember you forcing it on me. You were so excited to have found it. Boring stuff, nothing like his poetry. I read a few pages of

meaningless royal intrigue and set it aside. It’s still upstairs somewhere.”[…]Here the ghul hunter looked up at Litaz. “And you say you found this book boring, my dear?”

Litaz shrugged. “I did not read that far.” (p.163-5)

L’histoire est très linéaire.

- Début : des gens ont été massacrés par des goules

- Combat contre des goules

- Rencontre avec Zamia

- Re-combat contre des goules et Abou Nawas, Zamia blessée.

- Arrivée de Litaz et Dawoud, qui soignent Zamia

- « Je connais quelqu’un qui »

- Raseed va chercher du crimson quicksilver, affronte le Falcon Prince

- Adoulla va voir Miri et gagne le parchemin

- Dawoud va prévenir la garde sans succès

- Litaz connait Yaseer, qui décrypte le parchemin

- Oh non ! La prophétie ! Allons au palais!

- Rencontre avec le Falcon Prince, subjugation volontaire du prince

- Showdown

- Orshado arrive dans la salle du trône blesse le prince

- le Falcon Prince boit le sang du monarque blessé, gagnant des tas de pouvoirs

- Orshado est tué par Raseed et Abu Nawas est tué par Zamia.

- Conclusion

- Le Falcon Prince est au pouvoir, les gens savent pas trop si son régime sera meilleur (j’ai hâte de la suite pour la morale cynique et originale qui nous montrera que toute révolution reproduit les erreurs du passé!!!)

- Raseed veut poursuivre sa voie de derviche de l’ordre malgré son début d’amourette avec Zamia

- Litaz et Dawoud en ont marre de cette ville de cons et vont rentrer chez eux

- Adoullah demande Miri en mariage

- Fin.

Il n’y a pas beaucoup de progression, ou plutôt, ces progrès n’ont aucun lien avec l’histoire telle qu’elle se déroule devant nous. Litaz, Dawoud et Adoullah, ça se résume à « on est vieux on en a marre de se battre, on veut juste faire du sexe de vieux dans un coin », Adoullah allant même demander Miri en mariage, histoire de se caser. On ne voit pas sa réponse. L’arc de Raseed ? Son début d’histoire d’amour avec Zamia. Zamia ? Elle venge sa famille en tuant Abou Nawas.

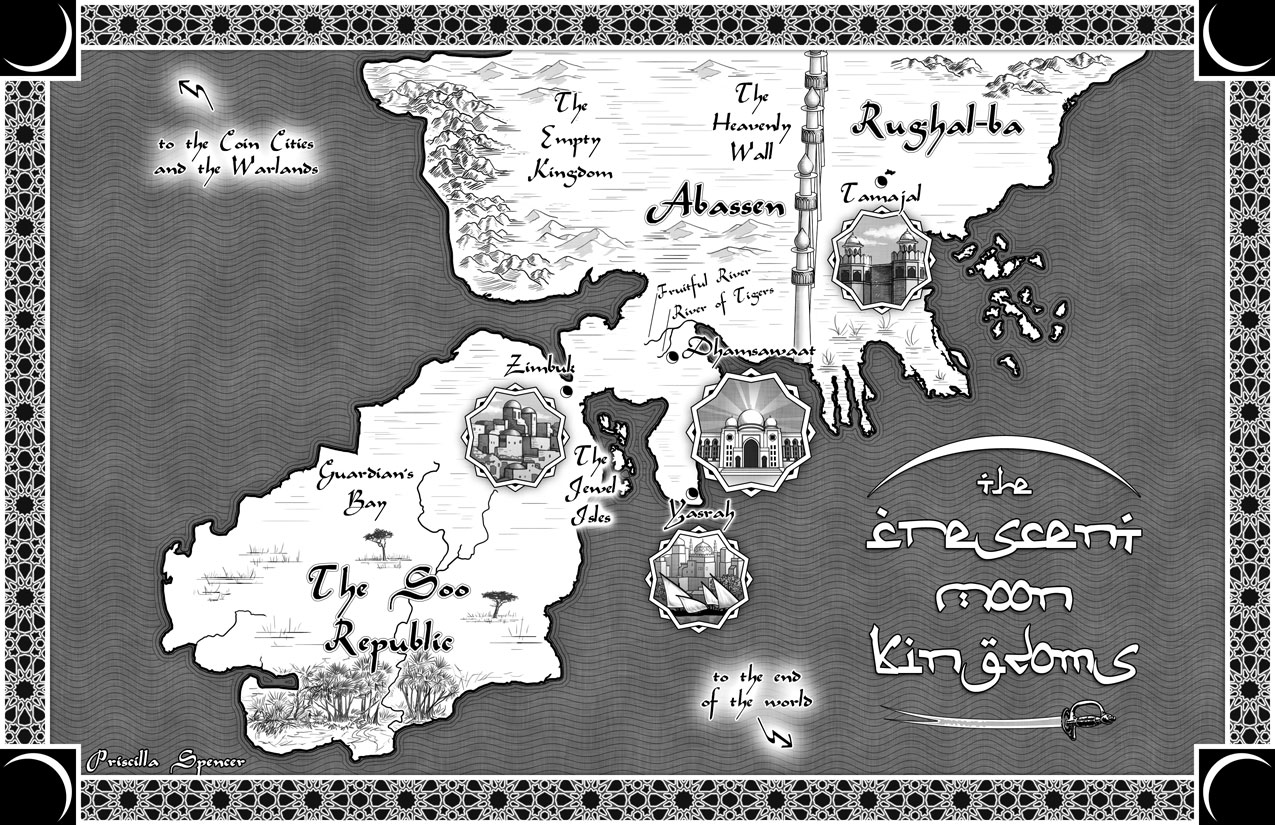

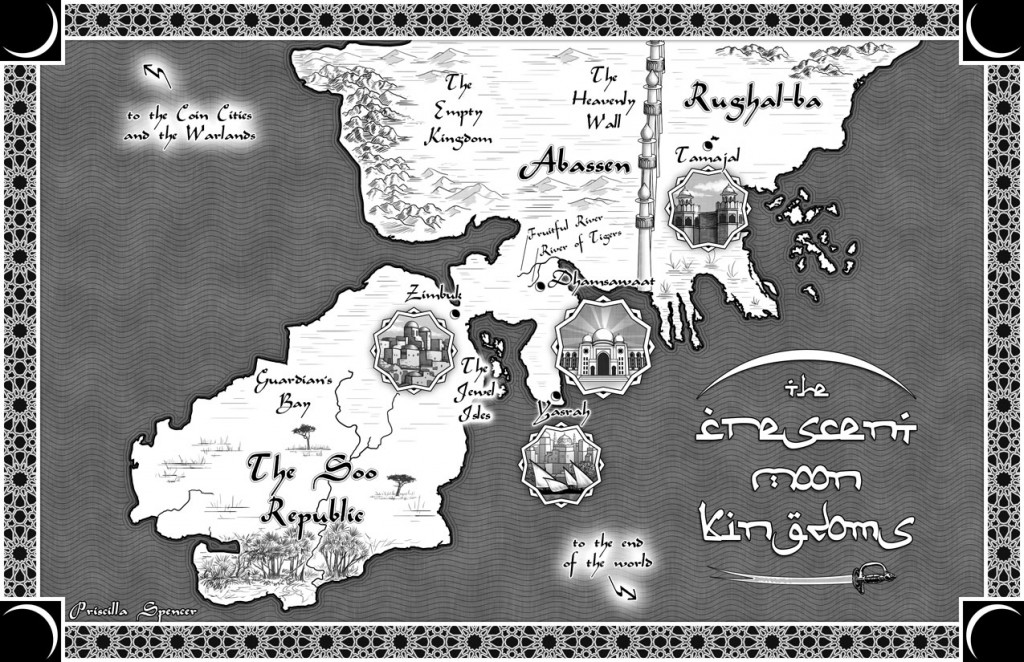

Adoullah est vieux et se plaint tout le temps, Raseed est un paladin loyal-bon, Zamia alterne entre la fierté et les pleurs ; aucun de ces personnages ne me semble vraiment intéressant. L’histoire est linéaire, tous les problèmes résolus trop facilement, par des emplettes inintéressantes. Je comprends le sentiment qui veut qu’on lise la transcription d’une partie de D&D laborieuse. En outre, le monde alentours, malgré les constantes allusions, n’est pas développé. La carte promettait plusieurs lieux :

Mais tout se passe (hormis les premiers combats) dans Dhamasawat. A la fin on s’interroge :

Other cities, the Soo Tripasharate, the High Sultaan of Rughal-ba— how will these men respond? The Crescent Moon Kingdoms have always been stitched together with delicate threads. (p. 359)

Oui je me demande comment ces lieux qui n’ont eu aucun impact sur l’histoire vont réagir, je suis palpitant.

Personnages féminins forts

Zamia alterne entre la fanfaronnade et la faiblesse. Elle braille contre Adoullah, puis fond en larmes. Elle fonce contre Abu Nawas, puis, blessée, passe le 10 chapitres alitée à se faire soigner, tout le monde lui recommandant l’inactivité, et puis… Et puis il y a ce passage :

Tears filled Zamia’s emerald eyes, but they did not fall. Raseed felt sick with knowing that he wanted—wickedly!—to go to her and to hold her as he had sometimes seen men hold women on Dhamsawaat’s streets. A rueful scowl spread across Zamia’s face. “I don’t know, Doctor. Each month for several days, when I am—when women’s business is upon me—I am unable to take the shape. (p.278)

Elle ne peut pas se changer en lion quand elle a ses règles. Ce qui en fait un peu l’inverse d’un loup-garou qui se transforme une fois par mois ? Ce n’est ni expliqué ni rationnalisé. Comme le fait que les chasseurs de goules perdent leurs pouvoirs quand ils se marient, elle perd ses pouvoirs une fois par mois. (???)

Miri est évoquée par les rêves humides d’Adoulla pendant les 100 premières pages avant d’apparaître enfin, et quand elle le fait c’est pour aider un peu Adoulla, montrer sa force et son indépendance en tant que proxénète, puis refuser leur passé amoureux commun, ils se pleurent un peu dessus. Ca m’a franchement fait penser au traitement des femmes chez Roland Emmerich. Vous savez, 2012. Dans ce film on a (comme souvent chez Emmerich) le scientifique un peu déconnecté du monde que tout le monde dit inutile[Erratum : je mélange tout Emmerich. Dans 2012, Jackson Curtis, joué par John Cusack, est écrivain de science-fiction et non scientifique, contrairement à Independence Day ou Le Jour d’Après qui ont les personnages de David Levinson ou Jack Hall] et là, on a son ex qui… Comment dire ? N’est pas traitée comme un personnage ? Elle est traitée comme un symbole du regret, des échecs du passé. A la fin du film, quand le scientifique neuneu contemple un monde sauvé, il peut prendre la main de son ex et se remettre avec, pour une deuxième chance, maintenant qu’il a prouvé sa valeur à travers ses exploits dans le cataclysme après que son mec actuel se fasse littéralement broyer dans des engrenages pour lui faire place. Miri est pareille, elle est le symbole d’une vie sans combat parce que dieu du ciel c’est trop dur d’être le dernier sauveur du monde chasseur de goules.

J’ai réussi à trouver une part de la review de Benjanun Sriduangkaew aka Requires Hate aka Winterfox, qui a parfois été retenue à son encontre comme un exemple de harcèlement dans le rapport de Laura Mijon. Une réfutation du rapport tente de la blanchir. En tous les cas, il m’a fallu consulter l’archive de la page web.archive de son article, étant donné qu’elle a tout viré et changé son robots.txt.

Tough, tough girl who melts into insecurity? Check. Tough, tough girl who displays emotional vulnerability (in Zamia’s case, even more rapidly than Jack)? Check. For more info on this betattooed lady, try Kyra’s Subject Fail at Ferretbrain. Now it’s possible Zamia isn’t as fiercely failtastic as Subject Zero/Jack–I imagine she doesn’t have Jack’s history of dodgy sex or even possible sexual abuse–but they come from the same place of male fantasy, roughly speaking: of being the one to melt her hard exterior, and get at the soft squishy center within. Maybe Raseed isn’t as creepy as male!Shepard, I don’t know, but it’s not a trope I like even one little bit. Zamia also loses the ability to shapeshift when she’s menstruating:

Tears filled Zamia’s emerald eyes, but they did not fall. Raseed felt sick with knowing that he wanted—wickedly!—to go to her and to hold her as he had sometimes seen men hold women on Dhamsawaat’s streets. A rueful scowl spread across Zamia’s face. “I don’t know, Doctor. Each month for several days, when I am—when women’s business is upon me—I am unable to take the shape.

So, like, do male lion shifters lose the ability to shapeshift when they get hard-ons? Have wet dreams? Something? Anything? Observe, once more, the emerald eyes and the tears: Zamia cries in front of men a lot. Barf. Fellow readers who have read farther than I assured me that this book fails the Bechdel Test, and that Zamia doesn’t exactly do the “relations with other women” thing. Please correct me if it proves otherwise.

Just to be, you know, fair I skipped ahead and came upon this exchange between Adoulla and his true love, the welcomingly curvy Miri–

She squinted in thought for a moment, then shook her head. “Perhaps…perhaps I could. But I’m sorry, Doullie, I won’t. That would require my making more contact with his people, and after he killed this last headsman.…No, it’s just too dangerous. The man has lots of right-sounding ideas,” Miri continued, “and I must admit, he is remarkably handsome. I’d wager you didn’t know that I once saw those calves very close up. Did you know? Never you mind where or when.”

She was trying to make Adoulla jealous. To upset him. It was working. He felt—not in a pleasant way—that he was a boy of five and ten again.

As you can see, women contort themselves around the male gaze. In a true teenage schoolgirl gambit, Miri tries to make him jealous. ‘Cuz that’s what women do. Our lives, why they revolve around TEH MENS. She doesn’t just throw up her hands either, she throws up “hennaed hands.” Not unlike how a woman, instead of simply smiling, might smile with “lipsticked lips.” It’s a bit like how Harry Dresden interacts with women, really.

At this point I’m quite positive that whatever Ahmed knows of “feminism” has been gleaned entirely from watching Joss Whedon. Sure, maybe I missed out about 130 pages of wonderfully nuanced, subtle gender politics the likes of which will do Ursula le Guin proud.

But I doubt it. Because if that’s the case, why are the first seventy pages so desperately fucking awful

[…]

I’ve read a WH40K tie-in that’s less heteronormative than Throne of the Crescent Moon. Low. Fucking. Bars.

In the end, even if I were to push aside all my issues with the gender and sexual politics, it remains that the writing is blisteringly awful. There isn’t a single sentence, or even a sentence fragment, in all the pages I read that stands out. There isn’t a single sentence that flows and coheres into some evocative, lovely imagery. I don’t think there are even sentences that’d sound good when read aloud. Not a single point of characterization is ever conveyed with anything like subtlety. Everything is delivered by anvils, consistently and constantly. Each piece of trivia is repeated five times; each excuse for character motivation is belabored; none of the character interactions compels, and not even the setting can hold my attention. I went in with minimal expectations: for something fun if not especially substantial or memorable. Instead I got something completely unreadable. 24% of this book was consumed before I called it quits, and I daresay that’s a far fairer chance than it deserves.

Je partage complètement l’agacement de Requires Hate même si n’ayant jamais pris connaissance de l’oeuvre de Joss Whedon je ne peux pas désigner ça comme du Joss Whedon Feminism.

Et franchement je m’en foutrais un peu si ce n’était que l’auteur parade littéralement en disant regardez comme j’écris de bons personnages féminins qui subvertissent des tropes. Heureusement, une bonne dose de méchantes injonctions sur Twitter nous a libéré de ce spectre des gentils types de 2011 qui paradent leur progressivisme — Requires Hate a peut-être été sacrifiée dans le processus.

Almanach punchlines, Traditions & Heavenly Chapters

Dans une tentative d’ajouter profondeur, lore et sagesse au décor, les personnages n’arrêtent jamais de babiller des proverbes, les sortant soit des Heavenly Chapters (le livre sacré de ce monde fictif) soit des Traditions of the Order, une sorte de code monastique qui régit la vie du Derviche Raseed :

The blade was two-pronged, according to the Traditions of the Order, “in order to cleave right from wrong.” (p. 40)

The true dervish needs no horse, said the Traditions. And his Shaykhs at the Lodge of God said that Raseed was the fastest dervish the Order had ever seen. He could run for miles without tiring. As far as pack animals went, the Traditions were equally clear: The true dervish needs no more than he can carry on his back. (pp. 51-2)

“Impressive, Doctor. But the Traditions of the Order say ‘Being my enemy’s enemy does not make you my friend.’ ” (p. 68)

Soit encore des proverbes de l’Ordre des chasseurs de Goules d’Adoullah.

When one faces two ghuls, waste no time wishing for fewer was one of the adages of his antiquated order.(p. 7)

True to the code of the ghul hunter, Adoulla had never married. When one is married to the ghuls, one has three wives already, was another of the adages of his order. (p. 211)

Damia a quelques proverbes bédouins aussi.

“This is all that I have of my father, though I will never wield it—for since I was given the lion-shape I foreswore other weapons. ‘My claws, my fangs, the silver knives with which the Ministering Angels strike.’ This is the old saying.” (p.73)

With my father against my band! With my band against my tribe! With my tribe against the world! The old Badawi saying echoed mockingly through her head. (p. 164)

Comme le dit cette review :

The kingdoms of the Crescent Moon feel alive because Ahmed has taken great care to imbue them with those little touches from « traditional sayings » to the use of poetry and proverb to set up character interactions. It is here where Ahmed’s fictional setting goes far beyond the mere appropriations of a culture discussed in the opening paragraph. There is nothing « exotic » about this setting; believable people occupy a setting that easily could be a home to historical fiction as it is to a sword and sorcery-style adventure

Mais non. Outre le fait qu’on croirait de nouveau voir des gens cambrioler des proverbes du monde réél, c’est assez agaçant. Peut-être que c’est parce que c’est beaucoup trop fait dans les 70 premières pages, mais c’est lourdingue, surtout les Heavenly Chapters.

‘O believer! If a man asks you to chose between virtue and your brother, choose virtue!’ (p. 24)

The Heavenly Chapters say ‘A starving man builds no palaces.’ ”

“They also say ‘For the starving man, prayer is better than food.’ ” (p. 27)

And if the Crescent Moon Palace crumbled tomorrow, God would love us still. ‘For yea, they are the kings of men’s bodies, but God is the King of Men’s Souls.’ ” The Doctor’s quoting of the Heavenly Chapters was punctuated by the smell of animals. (p. 50)

« The Heavenly Chapters say ‘Yea, though the flesh is scourged, the soul of the believer feels no—’

– Please, boy, no scripture quoting! » (p. 69)The Chapters say ‘The mightiest of men is but a slim splinter before the forest of God’s power.’ (p. 73)

[it] brings the Heavenly Chapters to my mind: ‘O believer! Look to the accident that is no accident!’ (p. 97)

“ ‘God’s mercy is greater than any cruelty,’ ” he quoted from the Heavenly Chapters. (p. 180)

Parfois, Adoullah semble citer les Chapters pour ses sortilèges,

God is the lightning that strikes thrice! (p.114)

En outre, ces proverbes me semblent parfois plus tenir de la chrétienté que du monde arabe :

Adoulla said a quick, silent prayer of thanksgiving. Still, “God helpeth most the man who helpeth himself.”

Adoulla risked grabbing for his satchel. » (p. 65)

On croirait lire « aide-toi, le ciel t’aidera » qui conclut une fable de la Fontaine, Le Chartier Embourbé (livre 6ème, 1692-4) même si on en trouve une version dans les fables d’Esope, plus précisément dans le Bouvier et Heraclès, que La Fontaine copie :

Un bouvier menait un chariot vers un village. Le chariot étant tombé dans un ravin profond, au lieu d’aider à l’en sortir, le bouvier restait là sans rien faire, invoquant parmi tous les dieux le seul Héraclès, qu’il honorait particulièrement. Héraclès lui apparut et lui dit : « Mets la main aux roues, aiguillonne tes bœufs et n’invoque les dieux qu’en faisant toi-même un effort ; autrement tu les invoqueras en vain. »

Le grec fut traduit différemment au cours du temps. Jeanne d’Arc l’aurait utilisée pendant son procès, Pierre Milot la traduit « Aide-toi et Dieu t’aidera » en 1646. Fleury de Mellingen traduit dans son L’étymologie ou explications des proverbes françois (1656) « Aide toi et Dieu t’aydera ». Tous semblent suivre de Mathurin Reigner (1573-1613) qui dans sa Satire XIII nous dit : « Aydez-vous seulement et Dieu vous aydera ».

Tout ça pour dire que, si on peut trouver des analogues dans le monde musulman, ça semble un proverbe chrétien.

Et la plupart des dits des Heavenly Chapters me semblent raccomodés de morceaux de Bible, en dehors des « O Believer! » coraniques. Pensez à Pulp Fiction (1994) de Quentin Tarantino, où on cite supposément Ezechiel 25.17 [youtube]

Ezekiel 25:17. « The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he who, in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of the darkness. For he is truly his brother’s keeper and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know I am the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon you. »

Ce passage est incohérent. Sur la fin, c’est Dieu qui parle, mais le narrateur évoque ses frères ? Dans les faits, le vers biblique est beaucoup plus court (peu de versets font un paragraphe entier), et s’adresse aux Philistins et Cherethites:

Et je déploierai sur eux de grandes vengeances par des châtiments de fureur; et ils sauront que je suis l’Eternel, quand j’aurai exécuté sur eux ma vengeance.

And I will execute great vengeance upon them with furious rebukes; and they shall know that I am the Lord, when I shall lay My vengeance upon them. (King James)

Dans le film, il n’est pas clair si Jules invente, s’il met de l’emphase, s’il a appris d’une bible particulièrement corsée, s’il se souvient d’un sermon (et inclut l’homélie avec le vers biblique) ou si lui même est en train de commenter Ezechiel quoiqu’il ait l’air de le citer. Je lis que ça a été piqué à un film de Sonny Chiba, Karate Kiba (The Bodyguard; 1976) et les discours pompeux sur à quel point Tarantino est profond pour avoir communiqué de façon difficile. Mais la plupart des gens semblent confus par l’adjonction puisque la citation fabriquée respecte le champ lexical biblique, rappelant certaines des citations les plus emblématiques du livre :

- Vallée de l’ombre vient du Psaume 23 :

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death

I will fear no evil, for you are with me;

your rod and your staff, they comfort me.

- « His brother’s keeper » reprend la défense de Caïn en Génèse 4.9 feignant de ce ne pas savoir ce qu’il est advenu de son frère : « And the Lord said unto Cain, Where is Abel thy brother? And he said, I know not: Am I my brother’s keeper? » (King James) en français : « Et l’Eternel dit à Caïn : Où est Abel ton frère? Et il lui répondit : Je ne sais, suis-je le gardien de mon frère, moi?«

Ahmed semble faire la même chose :

He recited scripture. “Though I walk a wilderness of ghuls and wicked djenn, no fear can cast its shadow upon me. I take shelter in His—”

The Heavenly Chapters died on Raseed’s lips as a man appeared before him. (p. 347)

Le registre de cette citations me semble à mille lieues du Coran, mais de même que la fausse citation de Pulp Fiction, reprend beaucoup des tropes, des lieux communs des Psaumeset :

- « I take shelter », Dieu comme refuge apparaît beaucoup dans ces invocations :

- « It is better to take refuge in the LORD than to trust in humans. » (Psalm 118:8)

- « But let all who take refuge in you be glad; let them ever sing for joy. Spread your protection over them, that those who love your name may rejoice in you. » (Psalm 5:11)

- « Whoever dwells in the shelter of the Most High will rest in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the LORD, « He is my refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust. » » (Psalm 91:1-2)

- « Though I walk », « Quoique je marche à travers un milieu inhospitalier je n’ai pas peur », de même fait penser au psaume 23, surtout quand « cast its shadow » rappelle la Vallée de l’Ombre.

- « Wilderness of ghuls and wicked djenn », pourrait faire penser à Job 30.29 : le narrateur cotoie deux espèces d’animaux sauvages, ou à certains passage d’Isaie où les « velus » dansent en Babylone.

- « I have become a brother of jackals, a companion of owls. » (Job 30:29)

- « She will never be inhabited or lived in through all generations; there no nomads will pitch their tents, there no shepherds will rest their flocks. But desert creatures will lie there, jackals will fill her houses; there the owls will dwell, and there the wild goats will leap about. Hyenas will inhabit her strongholds, jackals her luxurious palaces. Her time is at hand, and her days will not be prolonged. » (Isaiah 13:20-22)

Soyons charitable, le Coran, hérite d’une part de cette emphase et parle bien parfois de Dieu comme d’un refuge :

- « and Allah knew better what she brought forth, – « And the male is not like the female, and I have named her Maryam (Mary), and I seek refuge with You (Allah) for her and for her offspring from Shaitan (Satan), the outcast. » (3.36)

- « when Musa (Moses) said to his people: « Verily, Allah commands you that you slaughter a cow. » They said, « Do you make fun of us? » He said, « I take Allah’s refuge from being among Al-Jahilun (the ignorant or the foolish). » (2.67)

- « And if an evil whisper comes to you from Shaitan (Satan), then seek refuge with Allah. Verily, He is All-Hearer, All-Knower. » (7.200)

Et certaines citations des Heavenly Chapters sont plus coraniques

Then he stood, closed his eyes, and recited from the Heavenly Chapters, sprinkling out a dark green powder—mint?— with each Name of God he spoke. “‘God is the Seer of the Unseen! God is the Knower of the Unknown! God is the Revealer of Things Hidden! God is the Teacher of Mysteries!’ ” (p. 53)

Le Coran insiste bien sur le Coran insiste bien sur l’invisible »الغيب » : en fait le Coran insiste beaucoup sur l’exaltation, plus que sur le côté proverbes :

« And fight in the Way of Allah and know that Allah is All-Hearer, All-Knower. » (2:244) « (He is) The Knower of the Unseen, so He does not disclose His Unseen to anyone » (72:26) « All-Knower of the unseen and the seen, the Most Great, the Most High. » (13:9) « Knower of the unseen and the witnessed, the Exalted in Might, the Wise. » (67:72) « Say: Surely my Lord utters the truth, the great Knower of the unseen. » (34:48) etc.

…Mais la prière de Raseed ici émane clairement du Psaume 23.

Ahmed doit se fatiguer de sa propre écriture, puisqu’après septante pages, il tente l’ironie consciente :

[Zamia:] « ‘My claws, my fangs, the silver knives with which the Ministering Angels strike.’ This is the old saying.”

[Adoullah, thinking:] »God save us from the poetry of barbarians! » (p. 73)“All-Merciful God, is the holy man spitting pious sayings at you already?” he asked. “The sun is barely up! Don’t misunderstand me—his laconic little jewels are all inspiring enough the first couple of times you hear them. But after that they start to sound a bit pompous.” (pp. 83-4)

Et après tout, ce ressenti que j’ai eu de me faire bombarder de psaumes et d’almanach vient probablement plus de mon passif que du subconscient de l’auteur. Je suis certain qu’on me pointera des passages coraniques qui, sous une traduction ou l’autre, peuvent rendre compte des citations qu’il fit.

Mais mon problème n’est pas qu’Ahmed soit un faux musulman ou qu’il ait raté une occasion de musulmaniser. Il y a des raisons simples à cette similarité, et peut-être de bonnes raisons : premièrement, les traductions du Coran tendent à singer le vocabulaire et les affectations bibliques. Deuxièmement, c’est un roman anglais, destiné à un public occidental. Ce serait injuste de demander à un auteur seul d’inventer une convention de traduction coranique, qui n’évoquera rien au lecteur, ou de faire des traductions littérales boiteuses alors qu’il sait très bien quel est le registre vocabulaire du sacré pour son public.

Mais pour moi une promesse n’était pas tenue.

Pratique musulmane ? Théologie musulmane ?

Et ça ne se limite pas qu’aux proverbes.

Ok, ils disent « God willing » on sent que ça traduit inch’allah, mais quelles pratiques sont véritablement islamiques ? Se prosternent-ils pour prier ? Mentionne-t-on un jeûne ? The Feast of Providence a lieu au solstice d’hiver et fait plus penser à Noël qu’autre chose. (p.202). Leur livre sacré n’est apparemment pas divisé en sourates ou en livres puisqu’ils se contentent de citer de n’importe où dedans sans précisions. La seule histoire mentionnée est « l’histoire de Suri », dont rien n’est dit sinon que sa morale implique la clémence. Ce n’est pas très vivant. Peut-être que le but c’est de mentionner le religieux en passant, sans que ça devienne le sujet, mais du coup qu’y a-t-il de révolutionnaire à se servir de ça comme décor ? Quel mal cela fait aux clichés orientalistes ?

Autre souci : la nature de Satan, en islam est ambigüe, il est désigné comme un ange, mais fait de feu, ce qui en ferait un djinn, et en outre expliquerait sa rébellion puisque les anges ne sont pas spécialement doués de libre-arbitre. Là, on en fait un Traitorous Angel (son nom officiel et répété : pp. 12, 21, 40, 49, 70, 71, 99, 100, 170, 171, 177, 182, 185, 191, 201, 202, 207, 219, 221, 228, 269, 273, 274, 275, 276, 295, 296, 298, 306, 351, 355, 357) , pas un Djinn, qui sont aussi présents et mentionnés. J’ai toujours bien aimé le concept des djinns donc ça m’embête mais bon.

Plusieurs moments indistincts que je peinerais à expliquer me chagrinèrent, mais je doute que ce soient des reproches rationnels. Juste que ça a une saveur de moyen-orient, qu’on peut mettre des coupoles et des minarets sur la couverture, qu’on peut écrire avec une police d’écriture faux-arabe sur la carte, mais ça n’a pas beaucoup plus de saveurs que si ça avait été écrit par le premier orientaliste venu avec Wikipédia.

Aussi : c’est bien la peine de bazarder la fantasy chrétienne avec des dieux vaguement païens si c’est pour nous faire de la fantasy musulmane où les dieux égyptiens sont littéralement des démons alliés de Satan. Bofbof.

Le système de magie ?

La religion imprègne toutes les pratiques magiques, qui sont censées venir de Dieu. Ca n’aurait pas plu à Frazer et je dois dire que ça ne me plait pas beaucoup non plus. Le mariage annule les pouvoirs des chasseurs de goules (p.212) et Zamia perd ses pouvoirs quand elle a ses règles. Déjà que la magie absurde j’aime pas tant, si en plus c’est de la magie absurde approuvée par le stampel divin non merci. On dit que Zamia est angel-touched sans forcément évoquer ce que ça signifie, bref comme le reste du livre c’est plus frustrant qu’autre chose.

J’aimais bien certaines choses qui sont esquissées dedans mais le reste est tristement banal.

Conclusion

« Ahmed may just be a better reviewer or critic than he is a writer of fiction. It happens to the best of us, I suppose. Though, between him and Cindy Pon (and possibly Khaled Hosseini as well), it’s not looking promising for Americans writing about homelands they’ve never seen (or only lived in briefly). I say “they” but I guess I should say “we.” Being too far removed from the “national epic” might diminish the relevance of what we bring to the table. We’re foreigners in every place, even, perhaps, the imaginary countries in our heads. »

Captain Falcon (@psychoxnino), 25 avril 2012

Ahmed disait peu de temps après la sortie du livre qu’il écrivait deux suites et que le tome deux, The Thousand and One, serait disponible dès mi-2013. Deux ans après, il semble que ce soit maintenant prévu pour 2016. The Thousand and One semble centré sur les djinns, une de mes parts préférées de la mythologie islamique donc qui sait, j’y jetterai peut-être un oeil avec curiosité.

Peut-être que j’avais des attentes un peu trop élevées, mais le livre a littéralement été nominé pour un Hugo, pour un des prix les plus prestigieux de la SFF. Peut-être qu’ils sont juste affligé d’une soif si vague de diversité que n’importe quelle prose fit l’affaire, pour peu qu’on ait l’auteur qui aille avec, voire sans (l’orientalisme béat est effectivement un problème). Peut-être que je suis injuste. Quand je lis le travail des auteurs SFF cools du moments ou leurs critiques les plus acharnés (par exemple Sriduangkaew) je ressens beaucoup des mêmes agacements. Je ne pense pas que ce livre se démarque justement, c’est sa fadeur qui me l’a principalement rendu détestable, et pas aidé par la quantité de gens qui me disent qu’enfin j’y trouverais de la fantasy islamisée.

Aussi c’est un premier roman, donc la suite devrait être meilleure. Peut-être que la suite m’enchantera. Et peut-être que si je lis les orientalistes je verrai à que point ça peut être pire.

Autres reviews

- Scrivler

- Elitist Book reviews

- Requires Hate [archive d’archive]

- Of Blog

Répondre à Typhon Annuler la réponse